Social Security’s Longevity Insurance Protects Those with Uncertain Life Expectancies

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The insurance enhances Social Security’s role of offsetting Black/White inequality.

My colleagues have just completed a really interesting study pertaining to the progressivity of Social Security. The usual story focuses on money’s worth, highlighting the offsetting effect of two factors. On the one hand, Social Security helps Black individuals and those with less education – and therefore low earnings – through its progressive benefit structure. On the other hand, the value of lifetime benefits inherently increases for individuals who tend to live longer – White people and those with more education.

Regardless of how these factors balance out, though, the money’s worth approach neglects the longevity insurance provided by the program. Because Social Security provides a life annuity, it offers households protection against outliving their resources. The value of this protection increases with the unpredictability of their lifespan. It turns out that this longevity insurance is particularly important for Black households and those with less education, because, while these groups have lower average lifespans than others, they face greater uncertainty around their averages.

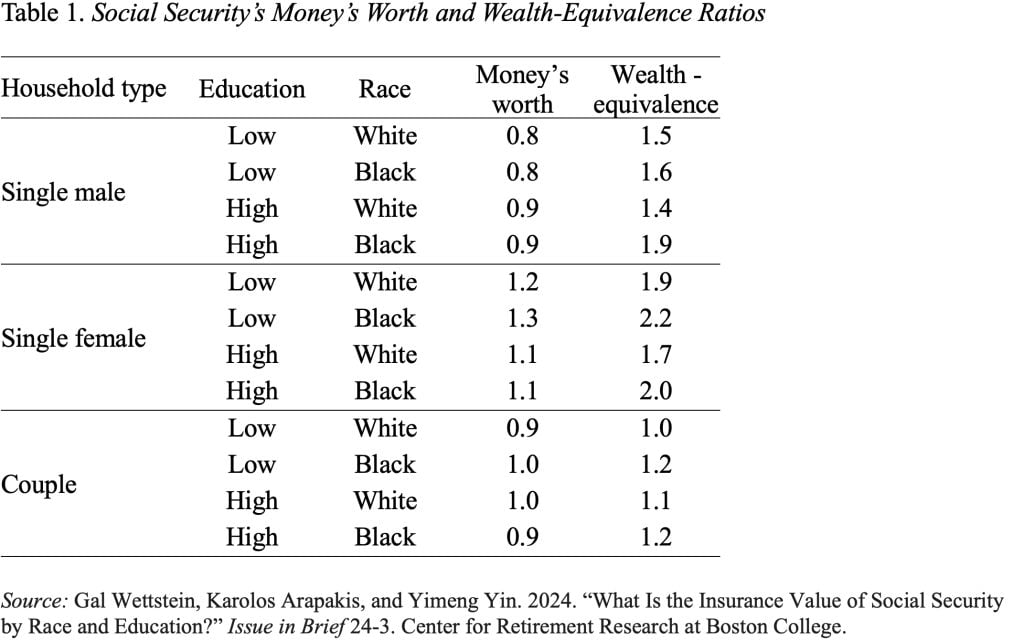

The analysis considers stylized households, differentiated by race (Black or White), education (low or high), and household composition (single man, single woman, or married couple). This process results in 12 stylized households that differ in terms of their mortality probabilities, lifetime earnings, pension income, Social Security benefits, and wealth at age 65.

The first step is to calculate the money’s worth of Social Security – the expected present value of each household’s benefits relative to the lifetime contributions. The next step is to measure the value of Social Security including longevity insurance. This analysis requires a complicated model to calculate how much more wealth households would need to be as well off in a world with no Social Security program as they are with the program. This measure is also related to lifetime contributions. Comparing these two measures shows how neglecting longevity insurance underestimates the value of Social Security to various types of households.

The results indicate that the wealth equivalence of Social Security retirement benefits is at least as great as the lifetime payroll taxes for almost all household types (see Table 1). This finding implies households generally prefer a world in which Social Security exists to one in which it does not.

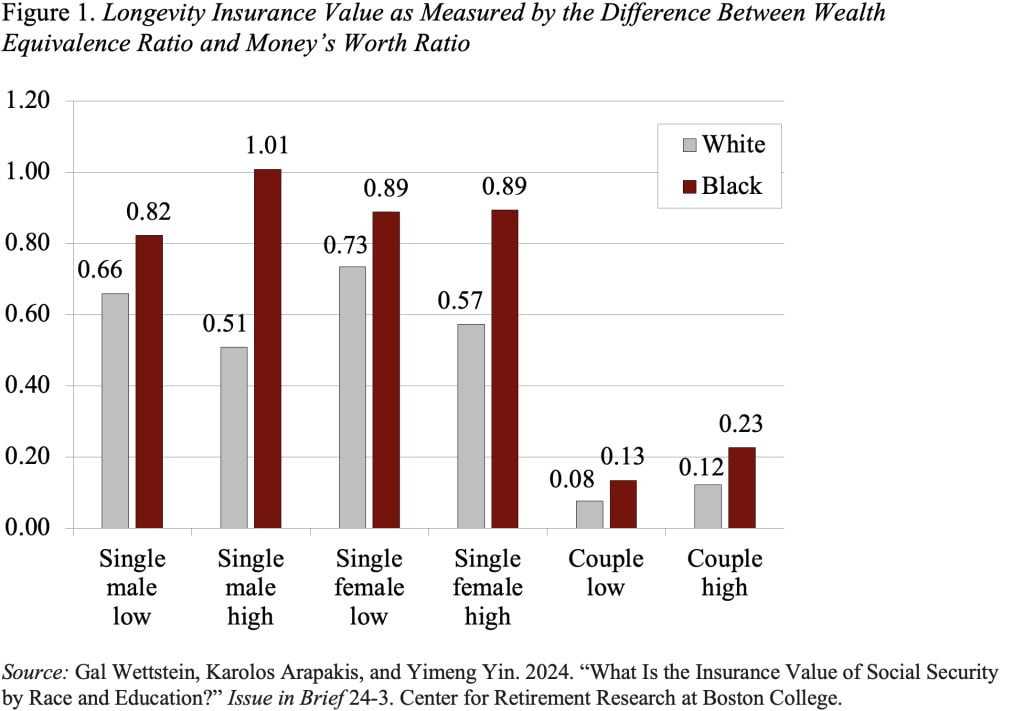

The difference between the wealth-equivalence ratio and the money’s worth ratio serves as an approximate measure of the longevity insurance value of Social Security. The results show that Black households consistently derive more insurance value from Social Security than Whites, reflecting the fact that Black households face greater longevity risk (see Figure 1). Also, as expected, single households value the longevity insurance more than couples, who can self-insure by transferring wealth after death.

The message here is very important. Money’s worth alone does not fully reflect the value of Social Security. People also value the insurance protection against running out of money. And the value of that longevity insurance is particularly valuable to Black households. In short, Social Security is an even more important equalizer than suggested by other studies.