What Long-Term Services and Supports Do Retirees Need?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

About one fifth will escape totally, and one quarter will require extensive care.

My colleagues and I just completed the first of a three-part series of briefs on the need for long-term care and the resources available to cover it. The possibility of needing care later in life is a real concern for late-career workers and retirees. People fear that they will either need to trade in their nest egg and independence to get support in a nursing home or languish in their homes with unmet needs. Fear of dependency may make retirees reluctant to spend their 401(k) balances, depriving themselves of necessities as they age.

The narrative that emerges from the academic literature, however, is more nuanced. Many people will experience only brief periods of needing care, and the burden in terms of the money spent on formal caregivers or the time spent by informal caregivers will be minimal. Some will experience the type of severe needs that most people dread.

This first brief is designed to help retirees, their families, and policymakers better understand the likelihood that 65-year-olds – over the course of their retirement – will experience disability that seems manageable, catastrophic, or somewhere in-between.

To meaningfully characterize the risk posed by a need for care in retirement, we were convinced that it was essential to jointly consider the severity and the duration of support needed. The challenge is that existing studies typically consider each dimension separately – by either examining support intensity at a specific point in time or support duration for a specified intensity level. Thus, we had to develop a system to sort care needs of varying intensity and duration into three categories: minimal, moderate, and severe.

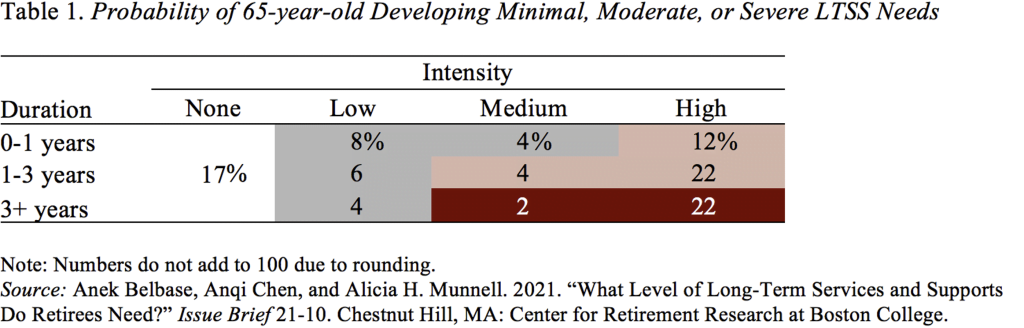

The sorting process involves four steps: first, support needs are defined as low, medium, or high in intensity; second, needs are classified as short, medium, or long in duration; and third, a two-dimensional matrix with intensity and duration is used to classify the nine possible types of care needs as minimal, moderate, or severe. Finally, we use 20 years of data from the Health and Retirement Study, a biennial longitudinal survey of Americans over age 50, to determine the actual lifetime care needs for individuals starting at age 65.

Lifetime needs are based on the individual’s most severe experience. That is, an individual who breaks her leg requiring minimal care in her 60s, then has a bout of cancer in her 70s requiring more than a year of support, and then develops dementia in her 80s requiring more than three years of care would be counted once and classified as having “severe” needs.

The results show that roughly one-fifth of 65-year-olds will die without ever requiring care and about one-quarter will have severe needs (see white and red shading in Table 1). In between these two extremes, 22 percent will experience minimal needs (gray shading) and 38 percent will experience moderate needs (pink shading). These results are consistent with prior studies.

The patterns across sociodemographic groups are as one would expect. Married individuals, those with some college or more, whites, and those who report excellent/very good health will need relatively little in terms of support, while single individuals, those without a high school diploma, Blacks and Hispanics, and those who report poor health will need a lot.

The big question is whether those who need help will have the resources available either in terms of family or friends to receive informal support or sufficient finances to pay for formal support. To answer that question, the next brief in our series will examine the caregivers and financial resources that are typically available for assistance, and the final brief will consider both the risk of needing support and the resources available in order to identify people who are particularly at-risk of experiencing needs they do not have the resources to meet.